Published

2 years agoon

The quest for its origins

The eighth continent of the world was hidden in plain sight for all this time, and it took scientists 375 years to find it. The land mass’s characteristics, however, remain a mystery.

A seasoned Dutch sailor, Abel Tasman was on a mission in 1642. He was sure that a massive continent existed in the southern hemisphere and was anxious to find it.

Europeans had an unwavering assumption that there must be a substantial land mass there, which they preemptively called Terra Australis, to balance out their own continent in the North. At the time, this region of the world was still mostly a mystery to them. The fixation had existed since the time of the Ancient Romans, but it would only now be put to the test.

So, on August 14, 1642 Tasman and two small ships departed from the Indonesian port of Jakarta, where his business was based, and sailed west, south, then east until they reached the South Island of New Zealand. His first interaction with the Mori inhabitants—who are believed to have arrived in the area centuries earlier—did not go well. On day two, a group of them set out in a canoe and rammed a small boat that was carrying signals between the Dutch ships.

The fate of the Europeans’ targets is unknown after they fired a cannon at 11 additional canoes. And there was the end of his expedition; Tasman gave the tragic spot the ironic name Moordenaars (Murderers) Bay and sailed home a few weeks later without having even stepped foot on this new continent. Although he thought he had found the big southern continent, it was obviously not the commercial nirvana he had envisioned. He never came back.

Tasman had no idea that he had been correct all along. There was indeed a missing continent.

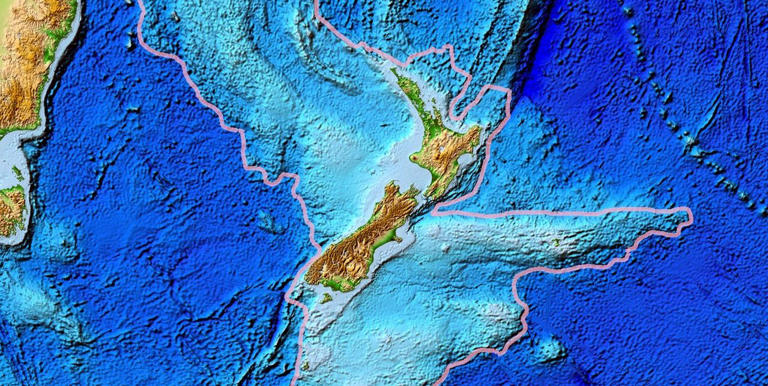

After discovering Zealandia, also known as Te Riu-a-Mui in Mori, a team of geologists made headlines in 2017. At 1.89 million square miles (4.9 million square kilometers), it is a sizable continent that is around six times larger than Madagascar.

The team boldly declared that there are more than seven continents, even though encyclopedias, maps, and search engines had long maintained that there are only seven. There are eight of them, and the newest one is the smallest, thinnest, and youngest in the entire world, shattering all previous records. Only a small number of islands, including New Zealand, protrude from the ocean’s depths, making up 94% of it. All along, it had been hiding in plain sight.

“This is an example of how something very obvious can take a while to uncover,” says Andy Tulloch, a geologist at the New Zealand Crown Research Institute GNS Science and a member of the team that found Zealandia.

The Scottish scientist Sir James Hector, who participated in an expedition to investigate a group of islands off the southern coast of New Zealand in 1895, acquired the first concrete evidence of Zealandia’s existence. He concluded that New Zealand is “the remnant of a mountain-chain that formed the crest of a great continental area that stretched far to the south and east, and which is now submerged” after examining their geology.

Despite this early success, there was little progress made until the 1960s about the possibility of a Zealandia. “Things happen pretty slowly in this field,” observes Nick Mortimer, the 2017 study’s principal investigator and a geologist at GNS Science.

A Strange Stretch

Zealandia was formerly a part of Gondwana, a supercontinent that once covered the entirety of the southern hemisphere and was formed around 550 million years ago. It was located in a corner on the eastern side, bordering a number of other countries, including the entirety of eastern Australia and half of West Antarctica.

Then, according to Tulloch, “due to a process which we don’t completely understand yet, Zealandia started to be pulled away” some 105 million years ago.

In comparison to oceanic crust, which is typically around 10 km thick, continental crust is often about 40 km deep. The tension caused Zealandia to become so stretched that its crust is currently barely 20 km (12.4 miles) deep.

But there are still a lot of uncertainties. The eighth continent is especially fascinating to geologists and somewhat perplexing due to its peculiar beginnings. For instance, it’s still unclear how Zealandia, which is extremely thin, managed to maintain its integrity and avoid breaking up into many small micro-continents.

Another unsolved question is when exactly Zealandia became submerged and whether dry land ever existed there. The ridges that are currently above sea level were created when the Australian and Pacific tectonic plates collided. Tulloch claims there is disagreement about whether the area was originally fully dry land or whether it has always been submerged save for a few small islands.

An Indication Towards Dinosaurs

The remnants of many fossilized land animals, including the rib bone of a large, long-tailed, long-necked dinosaur (a sauropod), a beaky herbivorous dinosaur (a hypsilophodon), and an armored dinosaur (ankylosaur), were discovered in New Zealand in the 1990s. Fossilized land animals are uncommon in the southern hemisphere. Then in 2006, some 500 miles (800 km) east of the South Island, in the Chatham Islands, the foot bone of a big predator, presumably a type of allosaur, was found. Importantly, all of the fossils were created after Zealandia separated from Gondwana.

These islands may have served as sanctuaries while the rest of Zealandia was drowned, as it is now, thus this does not necessarily imply that there were dinosaurs wandering across most of Zealandia. “There’s a long debate about this, whether it’s possible to have land animals without continuous land – and whether without it, they would have been snuffed out,” says Rupert Sutherland, a professor of Geophysics and Tectonics at the Victoria University of Wellington.

The Kiwi, a clumsy, flightless bird with whiskers and feathers that resemble hair, becomes one of New Zealand’s strangest and most adored residents, adding complexity to the plot. Oddly, its closest ancestor isn’t regarded to be the Moa, which belonged to the same group as ratites and lived on the same island until it became extinct 500 years ago. Instead, scientists believe that its closest related is the even larger elephant bird, which stalked Madagascar’s forests up until 800 years ago.

The shape of Zealandia is another unsolved puzzle

“If you look at a geological map of New Zealand, there are two things that really stand out,” Sutherland states. A plate boundary that runs along the South Island and is so significant that it can be seen from space is one of them, and it is called the Alpine Fault. The second is that New Zealand’s geology is strangely bent, as is the geology of the entire continent. The Pacific and Australian tectonic plates collide, dividing both along a horizontal line. The previously continuous ribbons of granite no longer line up and are now practically at right angles, as if someone had grabbed the lower half and twisted it away at this precise location.

That the tectonic plates shifted and, in some way, bent them out of shape is an obvious explanation. But the precise details of how and when this occurred remain a complete mystery.

Even if nothing else, the existence of the eighth continent in the world proves that, nearly 400 years after Tasman’s exploration, there is still much to learn.

Ayatollah Khamenei confirmed killed, as Tehran promises retribution

USA and Israel attack Iran, plunging Middle East into chaos

Union Budget 2026: The verdict from the Boardroom is in

Union Budget 2026: All the key announcements made by the FM

Maharashtra Deputy Chief Minister Ajit Pawar passes away after plane crash near Baramati

Deepinder Goyal resigns as Eternal CEO; Blinkit’s Albinder Dhindsa to take the helm